Honey Bee Sensory Superpowers: Smell

Smell, But Not Quite Like Ours

Describing one of a honey bee’s senses as “smell” can be misleading. While bees do detect airborne chemicals, this ability is far more than a sensory experience—it is the foundation of communication. Through pheromones, chemical signals exchanged between individuals, bees coordinate nearly every aspect of colony life. There will be a subsequent blog covering glands and pheromones, stay tuned!

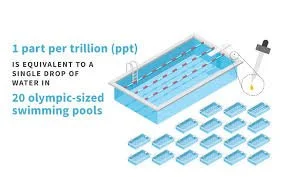

Just to give a concrete example of what one part per trillion (ppt) means!

Honey bees have an extraordinarily sensitive chemical detection system, capable of responding to certain molecules at concentrations as low as one to two parts per trillion. This allows them to navigate complex chemical environments both inside and outside the hive. Within the colony, scent signals queen presence, brood status, and colony membership; beyond it, smell guides bees to nectar and pollen sources across a wide diversity of flowering plants.

At the molecular level, bees detect odors using odorant receptors—proteins that bind specific chemical compounds and trigger biological responses. Humans rely on the same basic receptor system, making this one of the sensory mechanisms we genuinely share. While humans have more total odorant receptors than honey bees, chemical sensing plays a uniquely central role in bee biology. In honey bees, what we casually call “smell” functions as a finely tuned system for communication and navigation that underlies nearly everything they do.

Olfactory Receptor Neurons

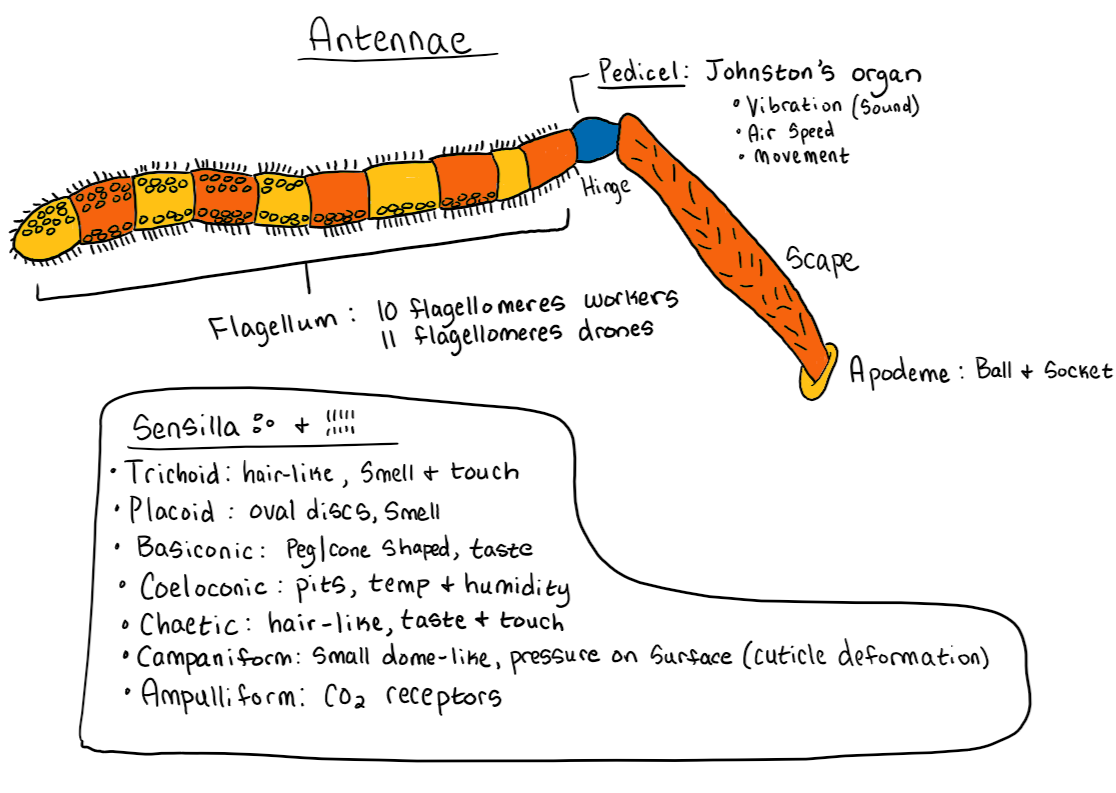

© Claudia Roller 2025

In the diagram of a honey bee antenna above, the small circles and hair-like structures covering each segment are called sensilla. These microscopic sensory hairs or pores are each specialized for different types of input. Some detect chemical signals such as pheromones and floral scents, while others respond to touch, taste, temperature, humidity, carbon dioxide, or pressure. This diversity makes the antennae far more than organs of smell—they are densely packed sensory hubs and the primary way bees perceive and interact with their environment.

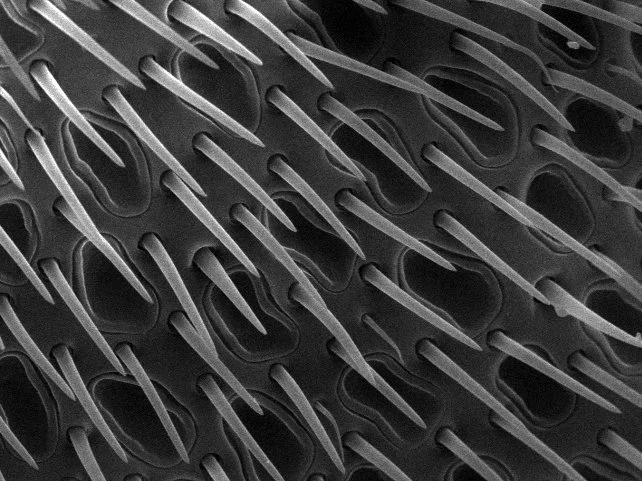

Odor detection occurs when airborne chemicals enter tiny pores in the sensilla. Among the most important for smell are pore plate sensilla (sensilla placodea), which are densely distributed across the antennae and highly effective at sampling the chemical environment. Inside each sensillum are olfactory receptor neurons (ORNs). When odor molecules bind to odorant receptors on these neurons, the chemical signal is converted into an electrical one and transmitted to the antennal lobe of the brain, where it is processed and interpreted.

Foraging, Navigation, and Memory

Foraging honey bees rely on smell long before they ever land on a flower. Floral scents act as chemical signposts in the landscape, helping bees locate rewarding plants once they are already in the general area identified by vision, memory, and dances performed by fellow foragers (more on bee dances in a later blog—stay tuned!). While color and shape guide bees at longer distances, scent becomes increasingly important at close range, where odor plumes drifting from flowers help direct bees precisely to nectar and pollen sources.

Bees are especially skilled at learning which floral odors are worth pursuing. When a forager encounters a high-quality food source, the scent of that plant becomes tightly associated with the reward of abundant nectar. On future trips, the bee is more likely to seek out flowers with similar odors. This odor–reward learning also reinforces recruitment: richer food sources lead to more enthusiastic dancing back in the hive, helping direct nestmates to the most profitable blooms. Together, these processes improve individual foraging efficiency and allow colonies to rapidly capitalize on strong nectar flows.

Smell may also play an underappreciated role in how foraging information spreads within the colony. Returning foragers share nectar with nestmates through trophallaxis—the mouth-to-mouth transfer of nectar shown in the video above—which conveys information about food quality and taste, while dances are the primary method for communicating location. Emerging research also suggests an additional layer of chemical communication: floral odors picked up during foraging can adhere to a bee’s cuticle (the outer surface of the body—essentially a bee’s “skin”) and be carried back to the hive. These cuticular-bound scents closely match the odors of the flowers being visited, exposing nestmates to the scent of current food sources simply through physical contact.

This chemical exchange may also serve as an early form of learning for younger bees that have not yet begun foraging. By interacting with returning foragers, these younger workers receive repeated exposure to floral scents before ever leaving the hive. In this way, experienced foragers may help prepare the next generation to recognize which odors signal valuable food sources. This early exposure allows new foragers not only to recognize familiar floral scents, but also to generalize—responding to new flowers that smell similar to previously rewarding ones—helping them adapt to changing floral landscapes without needing to learn everything from scratch.

Smell also helps guide bees home. While visual landmarks, magnetoreception, and the use of the sun as a compass dominate long-distance navigation (see our previous blogs on Magnetoreception and Sight), familiar hive odors and overall colony scent provide critical confirmation at close range—an especially important cue in dense apiaries where many hives are clustered together.

Colony Odor: who belongs and who doesn’t

For honey bees, recognizing who belongs in the colony and who doesn’t is largely a matter of smell. Guard bees at the hive entrance use close-range chemical inspection—using antennation and licking incoming bees—to decide whether an individual is a nestmate or an intruder. This rapid assessment is essential for protecting the colony from robbing and social disruption.

Each colony has a distinctive colony odor, formed from a blend of chemical cues found in the lipid layer covering a bee’s body (just like how human skin gets oily). While genetics contribute slightly, research shows that these cues are shaped primarily by the hive environment. Wax comb is especially important, acting as both a reservoir and a transfer medium for recognizing specific smells. Bees acquire colony odor quickly through contact with comb and nestmates, and even brief exposure can alter a bee’s chemical profile. Experiments swapping comb between colonies show that guard bees become more tolerant of non-nestmates when their chemical signatures converge—an effect that fades as the odors diverge again.

Colony odor also influences queen recognition. Workers can reliably distinguish their own queen from others using a combination of queen-produced pheromones and odors acquired from the hive. Queens introduced into foreign colonies are typically rejected unless workers are given time to relearn her chemical signature (usually by introducing the queen in a cage).

Sources

https://news.illinois.edu/honey-bee-chemoreceptors-found-for-smell-and-taste/

https://www.goldbio.com/blogs/articles/the-scents-of-honey-bees

https://theapiarist.org/smell-the-fear/

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC153582/

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7873095/

https://beeculture.com/a-closer-look-2/

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10886-020-01181-7